abandoned cities for the benefit of nature

The high tourist season is fast approaching and it is likely to resemble that of last year with very few international tourists, a lot of local tourists, a little bit of town, but more nature.

If the relaxation of health measures were to lead to a certain resurgence in the popularity of urban destinations, the constraints that will remain (distance, meeting limits) should continue to favor outdoor destinations.

One of our current studies on tourism in times of pandemic has enabled us to establish several observations on the Canadian tourism situation.

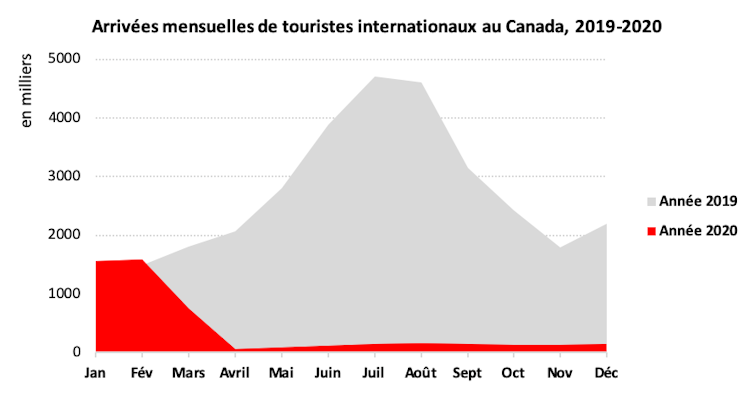

Last year in Canada, international travel restrictions to manage the spread of Covid-19 had immediate impacts with a drop of over half a million international tourists in March 2020, i.e. 92% less than the same period in 2019.

This decline has continued since summer 2020, in particular due to additional restrictions and constraints implemented by the federal government.

Authors’ compilation from Statistics Canada, Table 24-10-0041-01

In return, faced with the restrictions and constraints, approximately 20 millions of international travel recorded in 2019 for vacation and leisure purposes were likely to be transferred to domestic destinations in 2020.

Travelers stay at home

Part of this shift has, of course, taken place, as the share of Canadians who have chosen to visit inland destinations for vacation and leisure reasons has increased. increased by 4.4%. This is not surprising given that, even before the pandemic, the vast majority of travelers to Canada were already Canadians who traveled primarily to their province of residence.

For example, in 2019, domestic trips accounted for 89.2% of total tourist trips to Canada.

On the other hand, this propensity to travel “locally” increased with the pandemic, while the share of intraprovincial travel increased substantially in 2020. For example, for Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, these shares rose on average to nearly 94%.

This shift to local destinations helped increase the share of domestic tourism in total Canadian tourism spending from 78.4% in 2019 to 92.7% in 2020. However, it has not fully compensated for the losses associated with the absence of foreign tourists, who are usually smaller in proportion, but who spend more. Thus, the tourism spending in Canada fell from $ 105.1 billion in 2019 to $ 53.4 billion in 2020, a drop of 49.2%.

Cities are emptying

Metropolises like Montreal and Quebec, which are major tourist destinations in normal times and important gateways for international tourism, have experienced marked declines in tourists (especially foreigners) and in tourism spending.

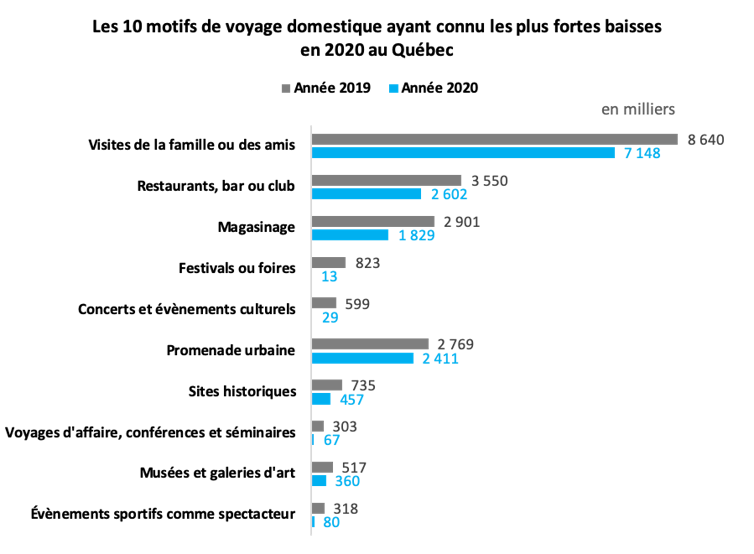

These decreases can be explained in particular by the drop in visits to family and friends as well as the drop in frequentation of restaurants, bars, shops, festivals, cultural events, museums, art galleries, sporting events and tourist sites.

Authors’ compilation using data from Statistics Canada’s National Travel Survey

Thus, in 2020, Montreal saw its number of international visitors drop by 94% compared to 2019 with the cancellation of festivals, conventions and conferences. The metropolis experienced its lowest occupancy rate for hotel establishments, around 15%.

AT Quebec, the cancellation of the Quebec City Summer Festival, which alone generates nearly 136,000 overnight stays in accommodation, deprived the City of $ 30 million. These difficulties have also been experienced by other Canadian metropolises such as Toronto, Vancouver and Ottawa.

The outdoors are popular

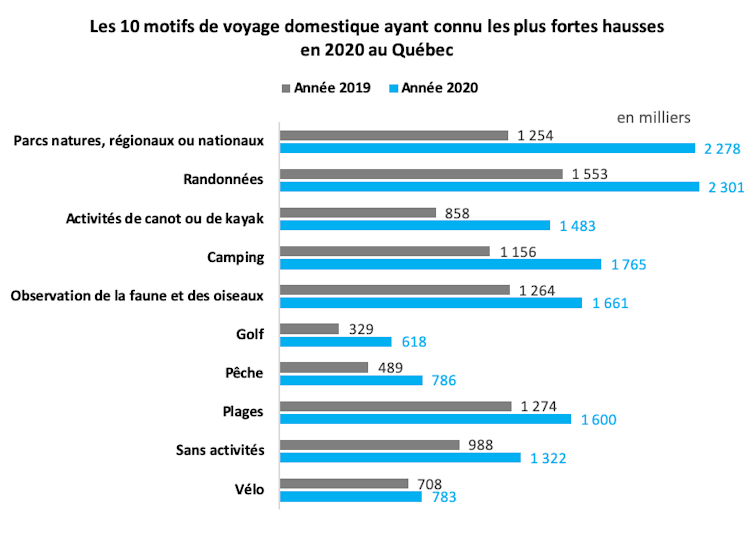

On the other hand, several outdoor destinations, outside major urban centers, have benefited from the increase in domestic tourism. This allowed them to significantly offset the loss of international tourists last summer. In Quebec, as in the other provinces, there has been an increase in trips for the purpose of visiting nature parks, hiking, canoeing or kayaking, camping, wildlife and bird observations, golf, fishing. fishing, beaches and biking.

Authors’ compilation using data from Statistics Canada’s National Travel Survey

(Too) popular destinations

Having become popular, these destinations located outside large urban centers did not all have the same reception capacities in the context of a pandemic.

Some had sufficient capacity in terms of space, accommodation and services. This is the case for outdoor destinations near major centers, which have been able to manage greater tourist flows, thus minimizing the negative impacts of the pandemic.

In Quebec, for example, destinations like Bromont and Mont Tremblant have taken specific measures to cope with a clear increase in demand, including the relaxation of urban rules to allow restaurateurs to install terraces on the street.

On the other hand, other popular destinations like Gaspe, Rawdon and Val-David were saturated and had to deal with hordes of disrespectful tourists. This saturation has manifested itself in several ways: a significant increase in road congestion, parking problems, non-compliance with sanitary measures, looting of certain public places and complaints from local residents.

Shutterstock

The influx of too many tourists has also caused shortages of food and utilities in some areas. Other examples of these problems have been identified elsewhere in Canada, notably in Glen Morris, Gray Sauble, Niagara-on-the lake and Northern Bruce as well as United States, at UK and in Scotland.

A new “geography of tourism”

At the dawn of the next tourist season, governments must intervene based on this new “geography of tourism” in times of pandemic.

Some measures have already been taken and it is important to continue them. We think in particular of federal programs financial assistance aimed at limiting the losses of tourist operators and enabling them to continue their activities. Quebec has also adopted numerous measures to support tourism businesses.

These programs are of paramount importance for cities like Montreal and Quebec, where the economic losses have been the highest. These programs are reflected in particular in wage and rent subsidies and in easier access to credit.

Establish limits

In addition, governments must continue to fund promotion of domestic tourism for less crowded recreational and tourist destinations in order to relieve congestion in those struggling with an excessive influx of tourists.

Municipalities must also establish acceptable limits related to their reception capacity. They could, for example, limit the number of camping spaces near tourist attractions, such as Gaspe or restrict access to certain trails or parks such as Sainte-Adèle and Piedmont.

The ban on converting private residences into tourist accommodation, as in Perforated, can also be considered. This type of initiative would not only respect the environment, but also the quality of life of residents.

To be effective, such measures will need to be closely monitored, for example by increasing the number of surveillance officers, as proposed in the City of Gaspé. The regulations in force must be applied, particularly with regard to fines.

The use of digital technologies is also one of the measures to be encouraged among tourist operators, because they can improve the upstream management of the influx of tourists. This involves, among other things, modernizing websites, installing counters or sensors to facilitate distancing, creating transactional platforms or developing mobile applications.

In short, the popularity of certain tourist destinations during the pandemic has led to opportunities to be seized. Efficient management of tourist flows is all the more important in a context where several regions aim to attract new residents and new businesses to their territory.